The World, Our Eyes, and Mind

The purpose of this article is not to teach knowledge, but to explore the relationship between the inner world, the visual world, and the external world, starting from how humans perceive the world.

First, let us boldly assume: there exists an “external world.” This world continues to exist stably even without contact from human (or other conscious animal) senses, and it changes according to natural laws—it is neither an illusion nor a fabrication. So, what exactly is this “external world”?

Second, we assume the existence of an “inner world”—one that each person carries within. Unlike the external world, the inner world is extremely sensitive, easily influenced by perspectives, statements, theories, and even emotions, thus becoming distorted or shaken.

Lastly, we assume the existence of a mediating layer between the inner and the outer: the “visual world.” As the name suggests, the visual world acts as a bridge through which humans relate the inner world to the external world. This article focuses solely on vision, excluding other senses such as touch and hearing. For humans, vision is carried out by the eyes. Here, we do not explore their biological structure, but simply regard them as closed observation tools—like the camera in your hand, capturing a portion of the world and offering it to us for contemplation and construction.

Now, let us take a rough look at these three concepts. As mentioned earlier, the world is vast and unfathomably complex; we cannot accurately depict its entirety. Instead, we choose a simple flower as our object of observation, hoping to sketch the contours of these three worlds and their relationships.

The External World

We see a flower: it is pink, with eight petals. Its center is yellow, radiating a touch of red outward. The flower as a whole is round, with slightly upturned petals that embrace the stamen. The petal edges are jagged like waves, extending faint creases outward from the center, slightly deeper in hue than the main pink body.

When sunlight hits the existence of the flower, it interacts with light—though we may not know how exactly—but the result is, pink and red colors appear in our visual field. These colors occupy a corner of space, without flooding the whole field. Their boundaries are clear, contours distinct.

So we may say, there is something here, and it undeniably exists. It occupies space, has form, emits color. We tentatively call it a “flower,” but must remember: “flower” is just a name we assign to this kind of existence. It is not the thing itself. The thing itself is something we can never truly see.

We cannot see existence itself. But that does not matter. What matters is: something exists, and we can perceive and recognize it through our senses. It says: I am here, and that is enough.

This is the essence of the external world: a vast system of existence, unimaginably complex, never fully graspable by us; but we can connect with it through various mediums—our eyes, ears, sense of touch—and learn: something is there. It is stable, and it follows certain rules.

From this, we may infer a principle: everything has shape, or we wouldn’t be able to see it; everything has color, or we couldn’t perceive it. Shape and color may be inherent traits of things—perceivable, stable—but we must still remember: they are not the existence itself, only its trace, which we can capture.

The Visual World

Do you know about pinhole imaging? I remember being fascinated by it as a child. With just a piece of paper and a tiny hole in the center, on a sunny day, you can aim the hole at a bright window and stand near a white wall indoors—you’ll see an inverted image of the outdoors on the wall: swaying trees, drifting clouds, breathtaking beauty.

This principle can even be used to observe a solar eclipse. I remember in 2008, when the eclipse passed over our village, I used a piece of paper to “project” the sun onto the ground. I could clearly see the dazzling sun gradually being eaten away, until only a glowing ring remained.

They say the human eye also operates by the principle of pinhole imaging, though in a much more complex structure.

However, apart from receiving light, I’m not sure what else the eye can sense. When I gaze at that flower, I don’t touch it—I’m separated by distance—yet I can still see it, and firmly believe that it truly exists.

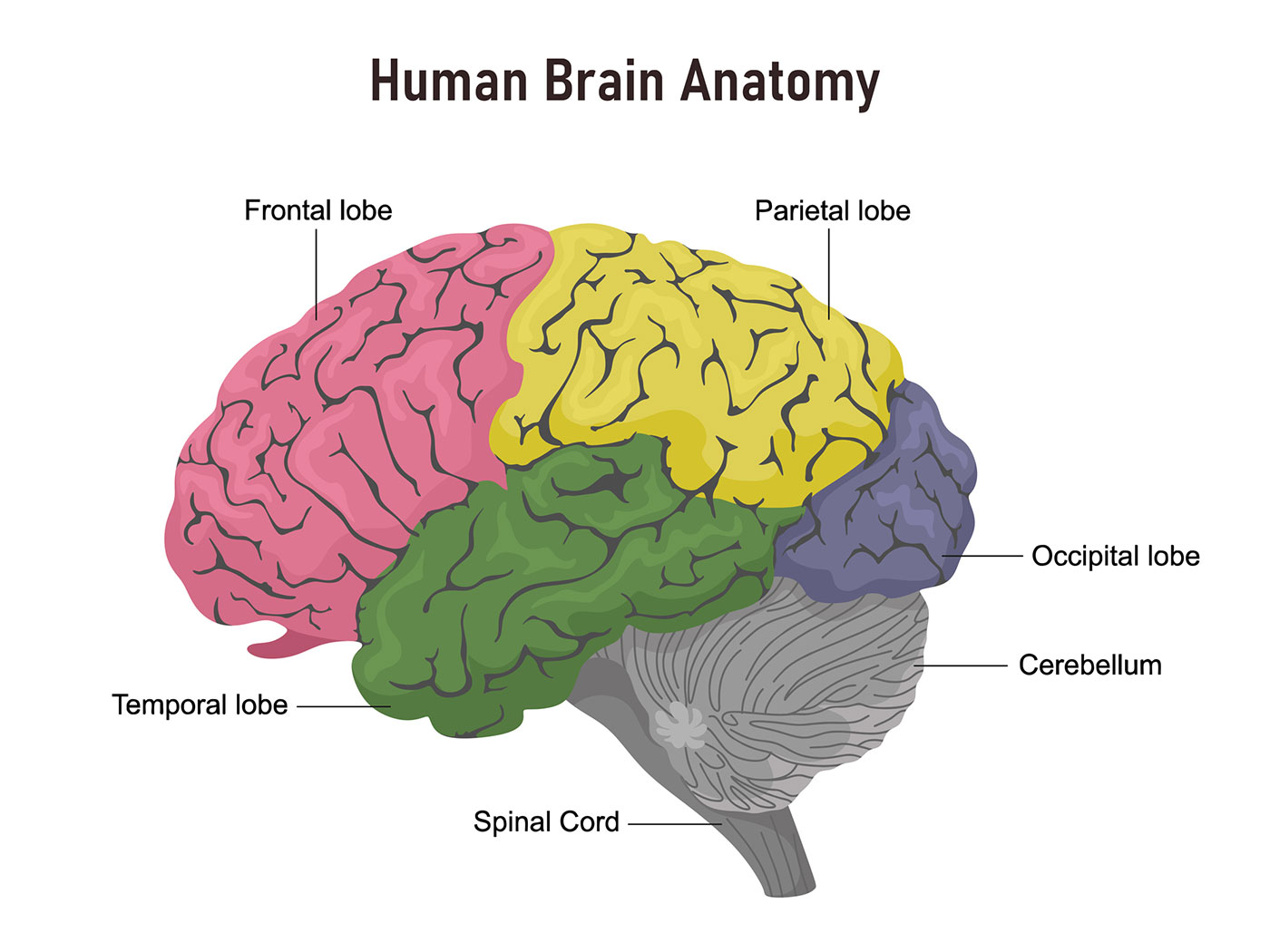

Current theory suggests the medium involved is light—or electromagnetic waves. Without a doubt, the eye receives these waves, projecting the light reflected by the flower onto the retina like a painting. This in turn stimulates the brain’s complex neural network, which we will not explore here. We can simply say: the eye’s task is to draw an image of the object, projected onto the retina of every being with sight.

As for how to understand that image, or the existence behind the image—that comes after vision.

The Inner World

Now, try closing your eyes.

Imagine the flower you just saw—can you “paint” its image again in your mind?

Very blurry, right? You can hardly distinguish the pink, and struggle to sketch the shape of the petals. What remains is only language: you say to yourself, “pink,” “round,” “jagged,” “yellow”… but the image itself refuses to come back.

Why?

Because when your senses disconnect from the flower—when real-time imagery ends—you’re forced to use another part of the brain to re-draw it. But the image is unstable, the colors ever-shifting. You may even start to doubt: What is pink, really?

“Pink” is just a word. It’s not light, nor pigment. It’s a code that evokes memory within your mind. When you think of it, you may recall a girlfriend’s pink stockings, a pink blouse—maybe it even excites you a little. I don’t fully understand the mystery behind this. I can only describe what I feel.

If you’re a front-end developer, you know that colors in a computer are represented by numbers or code. The “pink” in your brain is just like a code—it represents a sensory experience you once had but cannot now directly invoke.

For example:

<div style="background-color: pink">

This is a color named "pink" as you are seeing it! While closing your eyes,

it's a thing you cannot reach out.

</div>

The result looks like this:

This is presentation, not the thing itself. But what we need is often just that—presentation: a way to perceive, analyze, influence, or even create something.

So, what is in the inner world? It seems to have everything, and yet nothing.

We say it has everything, because we can let our thoughts roam freely; we say it has nothing, because all it holds are vague “contents”—far from reality, lacking in concrete imagery, and certainly not the thing itself.

Thus, I can only say: the inner world is made of concepts and notions.

- Concepts are collections of names—knowledge, classifications, definitions about things and their relationships.

- Notions are more subjective—impressions, opinions, feelings—often vague and hard to put into words.

The difference can be seen as:

| Term | Characteristics | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Notion | Subjective, emotional, value-based, vague | “His notions of education are very traditional.” |

| Concept | Objective, logical, systematic, abstract | “The concept of ‘freedom’ is hard to define.” |

You can think of the inner world as a block of code—with logic and structure.

A computer can interpret the meaning of pink and display it;

Humans can map internal language to the external world, like pointing to a flower and saying: “Look, it’s pink.”

A computer presents its code via the screen. Humans present the inner world through paper, paintbrushes, or language.

Reading Materials

Chapters:

Sparking Interest (Introduction and Critical Thinking)

- Introduction

- The World, Our Eyes, and Mind

- Color, Space, and Time

- How the Brain Constructs Space and Perceives Motion

- WebGL: Bridging Virtual and Reality

- Shader: The Sculpting Knife of Pixels

Mathematical Foundations (Graphics Math)

- Coordinate Systems and Vector Basics (Cartesian and Homogeneous)

- Vectors and Matrices: Translation, Rotation, and Scaling

- Projection Matrices and Perspective Projection Principles

- Normal Vectors and Lighting Basics

- Curves, Surfaces, and Animation Interpolation

- Intuitive Linear Algebra in Graphics

Introduction to WebGL

- What is WebGL?

- Relationship Between OpenGL and WebGL

- Vertex and Fragment Shader Concepts

- GLSL Writing and Debugging Basics

- Drawing a Triangle on Canvas

- WebGL Rendering Pipeline and State Management

Three.js Fundamentals

- Creating Scenes and Renderers

- Cameras and Controls

- Geometries and Materials

- Lights and Shadows

- Animation and requestAnimationFrame

- Mouse Interaction and Raycaster

- Loading Models and Textures